Historically, biologists viewed the mitochondria – the powerhouses of our cells – as bystanders in evolutionary and ecological processes. This view is quickly being overturned. Despite encoding just a small number of proteins, the genes of the mitochondria have been linked to processes such as the evolution of sex differences, adaptation to environmental stress and changing climates, ageing, and even speciation.

Mitochondria and evolution

While scientists have discovered much about the biology of mitochondria, very little is actually known about how natural variation in the set of genetic instructions (the DNA sequence) found within our mitochondria affect our day to day lives, particularly in terms of our likelihood of having certain diseases, problems with conceiving children, or prospects of living long and healthy lives.

Recent discoveries have indicated that the combination of mitochondrial genes we carry (our mitochondrial “genotypes”) affect all of these processes.

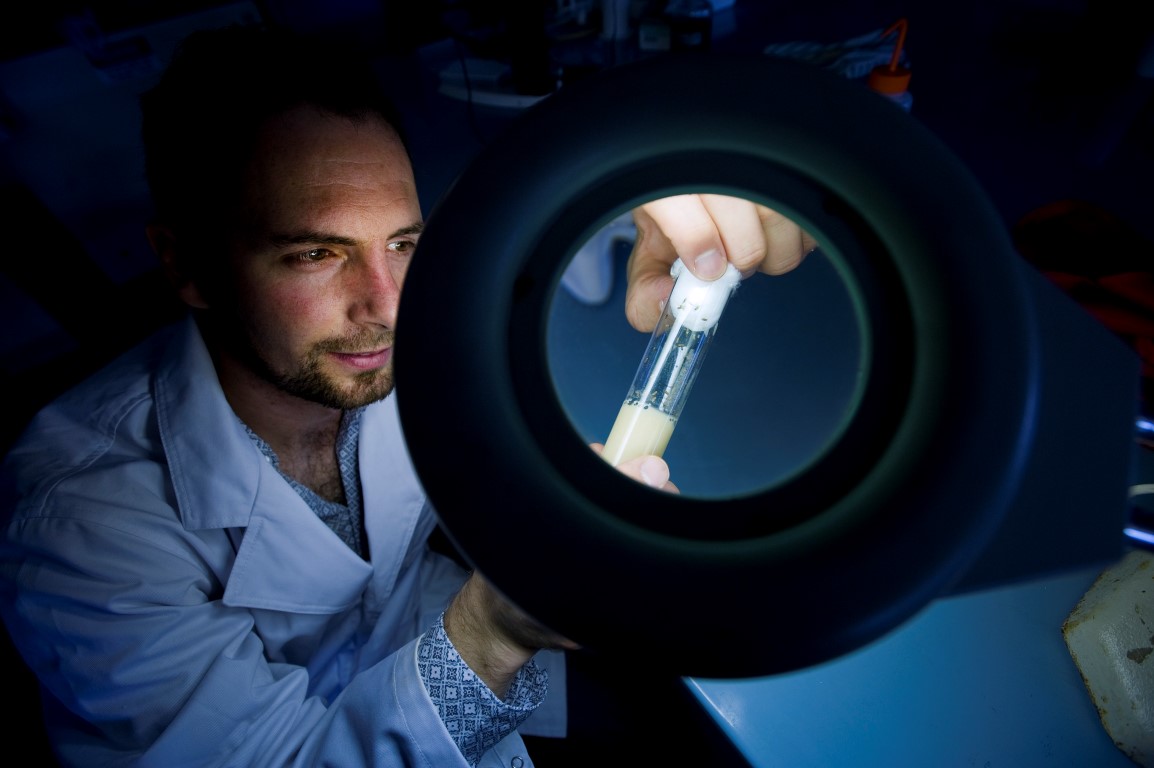

In our lab, we study mitochondrial contributions to evolution and ecology.

We use methods drawn from diverse fields of biology to address fundamental gaps in our knowledge.

Recently, our research demonstrated that the maternal inheritance of the mitochondria is bad news for males – because it facilitates the accumulation of male-harming mutations within the mitochondrial DNA that basically avoid the watch of natural selection.

These mutations affect fertility and even patterns of aging in males but not in females, and this might help to explain patterns of male infertility in humans, and why females generally outlive the males.

We are interested in the general co-evolutionary dynamics of the mitochondrial and nuclear genomes. Our mitochondrial genes contribute to encoding life’s most important biological function – oxidative phosphorylation (OXPHOS) – which is responsible for more than 90% of our energy production.

However, OXPHOS ultimately depends on finely coordinated interactions between genes dispersed over two obligate genomes – nuclear and mitochondrial. Fundamental genetic differences between these genomes set the stage for perpetual inter-genomic – perhaps even sexually antagonistic – evolutionary conflicts over optimization of our biological function.